The whooping crane is one of North America’s most majestic birds. Standing five feet tall, with a seven-foot wingspan, the bird’s snow-white plumage, black legs, and red spot on its head make it unmistakable. Its five-foot height makes the whooping crane North America’s tallest bird. The average weight of the bird is between fifteen and seventeen pounds. The whooping crane’s lifespan is estimated to be twenty-two to twenty-four years in the wild.

As many as 20,000 whooping cranes were once found throughout North America. But, by 1941, habitat loss and unregulated hunting had reduced the whooping crane’s numbers to less than two dozen individuals in the wild.

Like other cranes, the Whooper is noisy; the word “crane” comes from the Anglo-Saxon “cran,” which means “to cry out.” Two distinct migratory populations summer in northwestern Canada and central Wisconsin and winter along the Gulf Coast of Texas and the southeastern United States, respectively. Small, non-migratory populations live in central Florida and coastal Louisiana.

In their Texas wintering grounds, this species feeds on various crustaceans, mollusks, fish, small reptiles, blue crabs, and aquatic plants. Potential foods of breeding birds in summer include frogs, small rodents, small birds, fish, aquatic insects, crayfish, clams, snails, aquatic tubers, and berries. Waste grain, including wheat, barley, and corn, is an important food for migrating whooping cranes.

Although this species has been saved from extinction, the whooping crane remains the rarest of the world’s 15 crane species. It is classified as “Endangered” on both the U.S. Endangered Species List and the IUCN Red List, as well as the State of the Birds Watch List. These majestic cranes are monogamous and mate for life.

Mated pairs perform an elaborate dance display during courtship, with leaps, wing flaps, head tosses, and flinging of feathers, grass, and other small items. The whooping crane breeds in freshwater marshes and prairies. They are found in saltwater marshes, shallow lakes, and lagoons on migration and in winter. They build a nest where the female usually lays two eggs. Both sexes share incubation and chick-rearing duties.

Despite the fact that most pairs lay two eggs, only the first-hatched chick usually survives unless habitat conditions are good. Food availability and predator abundance are major factors in chick survival. Whooping cranes are slow-maturing and do not usually begin to breed until they are 4 to 5 years old.

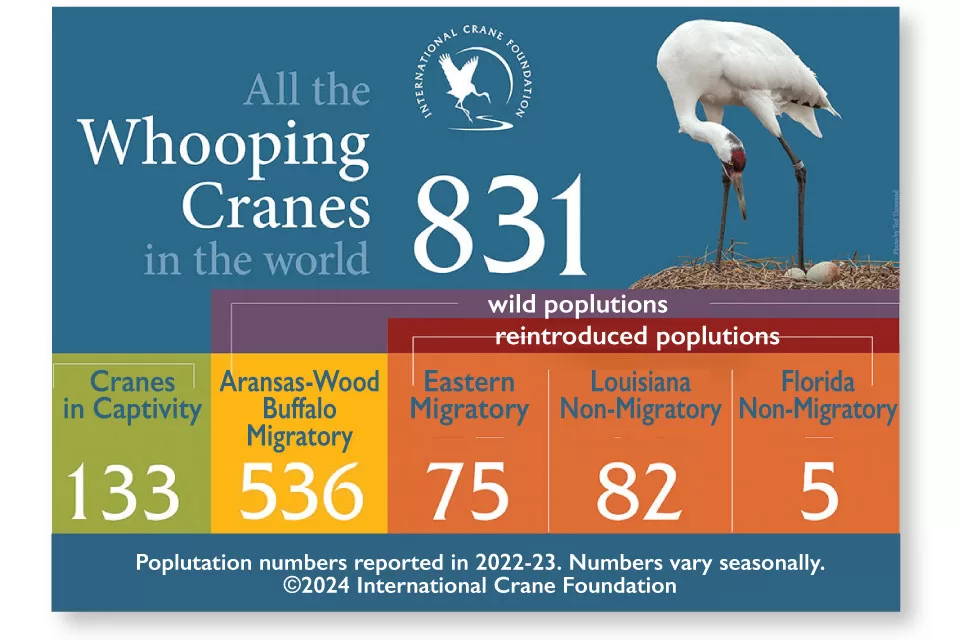

For the first time since the late 1800s, there are more than 500 whooping cranes in the population that winters in south Texas. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service aerial surveys counted 505 cranes in and around the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, Texas in 2018 as a part of their annual winter survey, a 17 percent increase from the previous year. These cranes, which migrate to Aransas from breeding grounds in Canada’s Wood Buffalo National Park, comprise the largest of four populations of endangered whooping cranes left in North America. The Aransas-Wood Buffalo group is the only self-sustaining whooping crane population that breeds and migrates without human assistance.

Whooping cranes as a species remain at very real risk of extinction and recent events highlighted the ongoing risks to whooping cranes’ continued recovery. Loss of habitat, climate change and weather conditions such as storms and hurricanes, are the main concern for keeping the whooping cranes from extinction. Their many potential nest and brood predators include American black bear, wolverine, gray wolf, mountain lion, red fox, Canada lynx, bald eagle, and common raven. Golden eagles have killed some young whooping cranes and fledglings. The bobcat has killed many whooping cranes in Florida and Texas.

The Nature Conservancy purchased a conservation easement on 2,162 acres of Falcon Point Ranch, in Calhoun County. While the only naturally migrating flock of whooping cranes nest in Canada, each winter the flock makes the 2,400-mile trip south to spend the season on the Texas Gulf Coast. Falcon Point, which is encompassed within the Welder Flats near San Antonio Bay, lies within a popular area for wintering whoopers. The Conservancy has acquired land to help expand the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge and establish the Matagorda Island National Wildlife Refuge, projects that have helped conserve some of the last remaining habitats in the world suitable for the wintering whooping crane.

The International Crane Foundation raises whooping crane chicks for release into the wild. It begins with a few precious eggs and ends with young whooping cranes ready for life in the wild. It is a very involved process that requires a tremendous amount of research and dedication. It is a fascinating and interesting process they have developed and well worth the time to visit the website and videos they provide.

There are numerous organizations that are working to protect the whooping crane including the International Crane Foundation, the Nature Conservancy, American Bird Conservancy, and the National Audubon Society. We encourage you to visit their websites and learn more about the extraordinary efforts to save the endangered whooping crane. In each issue we include an article about the world’s endangered species and the importance of pre-serving the species to avoid them becoming extinct. Each species contributes to the world’s environment and it is important for us to protect and nurture these creatures.

The whooping crane and its history has struck a very emotional chord in me. It is hard to believe that at one point there were less than two dozen on this earth. I think it is our responsibility to help raise awareness and funds to assist in these efforts. There are many ways to do this and we have highlighted some of our thoughts on ways each of us can help. It is so important and such a wonderful thing to do.

Raising Awareness & Funds